Category: Literature

Coming Into a New Community: Juneau piece by piece

In Istanbul I didn’t see the play “Faust” in Turkish, though it was always one of those stories with which I felt I “ought” to be familiar; “The Bodyguard” was playing when we lived in West Germany but only in German, a language I didn’t have the chance, at thirty-eight, to learn:

when I heard the Perseverance Theatre was going to show “They Don’t Talk Back”, I knew that – yes, even though we had a five month old daughter and didn’t know anyone else in the town to watch her, and probably wouldn’t leave her with anyone that long yet anyway – we’d find a way to go.

She attended a concert in Holland in utero, and we did take her to a comedy show when she was a month old (cramped venue, but Ted and Christina were visiting and we wanted to do stuff) and even ended up on one of the comics’ Twitter feeds, but how we’d do a play with her had us stumped.

First, we thought we’d just go to separate shows – Jake would go Thursday, I’d catch the Sunday matinee – but as he works long hours during the week, the weekend is our time together and that was how we wanted to spend it. A special matinee on Saturday was announced and we got tickets.

Despite leaving over an hour early we still walked into the darkened theater a bit late. Jacob had reserved seats near the door and I was happy to see there was another woman with a tiny baby sitting in the next row. Imogen was sound asleep in her car seat.

When she woke up halfway through the first act in the cozy theater, I simply got her out of her seat and moved her to my lap. She liked the drums and dancing; she seemed to be actually following the lead actress’s monologue… the one thing she didn’t quite understand is that you have to be quiet.

We think she liked the energy of the play and that is why she started cooing, but at any rate I ended up first standing in the back, and then sitting just outside the theater on a comfy couch for the second act so Imogen could coo without distracting art patrons.

The woman setting up coffee and snacks, and running the theatre, asked Imogen’s name, and when I also mentioned her nickname (Squigs), the woman painted a lovely picture of Imogen being on a talk show someday, divulging her early nickname to chuckles from the crowd.

When Jacob came out with our things, I told him he should stay in and watch, and that we were content to have seen as much as we had, the woman told me that I should come back the next day and catch the second act. I thought this very kind of her and decided to do just that.

At this point you may be wondering what the big deal is about this post: “okay, you went to a play with/without your baby, got it,” but if you’ve ever moved to a new city and/or shared a tiny space with just your husband and baby, you have an idea what is was like to attend a play by yourself.

It took about thirty seconds for me to get completely lost (in the good sense) in the play. A “coming-of-age” story and so much more about a (Native) Tlingit family, a mother who lost a daughter; weather, music: I felt at once a part of my new community, as if it showed itself just to me.

When I left, the woman who’d told me to come back told me she was so glad I had made it (seriously, why did she even care?), and (I realized after I got into the car how much I meant what) I said, “I can’t imagine if I hadn’t.” Then, she said, “your daughter is precious.”

Thank you Perseverance Theater and Juneau!

Please purchase my poetry chapbook!

Hello friends,

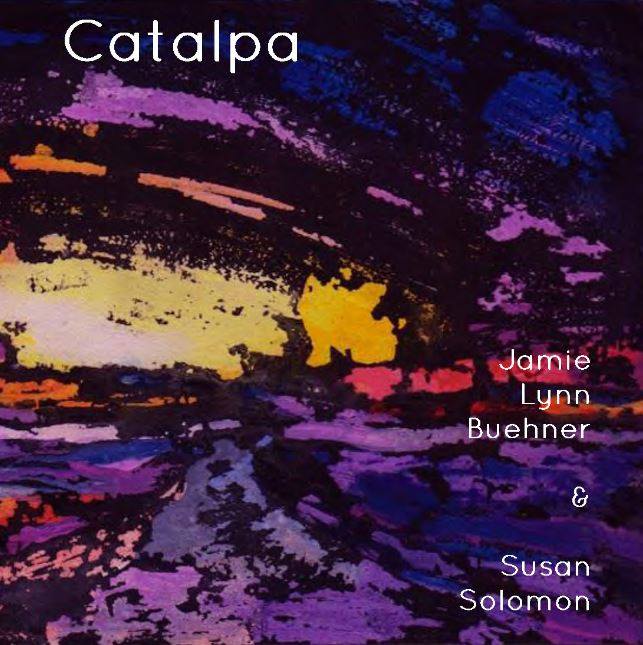

My second chapbook, a collaboration of poems by me and paintings by my dear friend and graduate school colleague Susan Solomon, has been made available here through Red Bird Press.

It is entitled Catalpa after the tree and the title poem. For the rest, you’ll just have to see for yourself!

It would mean a lot to us if you would support our project by buying our book and/or sharing this link.

Also, please let me and/or Susan know what you think!

Lots of love,

Jamie